There never was a publication called the 'Kirkliston Clarion', but had such a newspaper actually existed, its front page may well have looked something like the example above. It reflects some of the initial reaction in the national press to the news of a mail coach robbery which most certainly DID take place on Saturday, 18th December, 1824 outside the Kirkliston Inn, better known as Castle House today. Three packets of banknotes to the value of £7,000 and destined for various Edinburgh banks were stolen. A modest sum perhaps? Not at all! Adjusting for inflation over 200 years since the robbery, the sum would be worth £1,000,000 in today's money!

The following story charts which your author believes to be the most plausible account of what took place on that fateful day. He has drawn on evidence presented at the High Court in Edinburgh the following year, but has formed his own conclusions regarding the planning and enactment of the robbery that he considers was an 'inside job'. Where possible, actual names of persons involved, locations and timings have been employed. Elsewhere, 'creative licence' has been employed to complete the tale. When you have read the whole story and the trial transcript at the end of Part 2, please feel free to judge for yourself whether your author has traduced the reputation of the mail coach guard, or whether you are able to form an entirely different interpretation of events.

*****

THE GREAT KIRKLISTON MAIL COACH ROBBERY, 18th DECEMBER, 1824

The passengers seated atop the mail coach pulled their cloaks and mantles ever-closer around their bodies in a forlorn attempt to keep out the worst of the cold December air. The four-hour journey to Edinburgh was going to be a feat of endurance and potentially lethal with the temperatures certain to drop even further as the short winter day gave way to darkness. Already 15 minutes later than their scheduled three o’clock departure, they were becoming ever impatient to set off with the gloaming creeping in on this Saturday afternoon. The four inside passengers, despite being sheltered from the worst of the elements, were packed cheek by jowl and just as anxious to be on their way. There was still no sign of the coach guard whose absence was delaying departure and raising the hackles of the driver who was not looking forward to negotiating the appalling roads in pitch darkness. Lit only by the thin light of gig lamps to show the way, many an accident could happen in such circumstances, especially if the team of four horses took the head and got out of control.

At last, William Home the mail coach guard emerged from the Post Office. Having taken delivery of the third and final parcel of bank notes from the agent of the Leith Banking Company he made his way swiftly to the coach. The other two parcels had been from the Bank of Scotland and the Commercial Bank, just a couple more banks in an age when numerous banking companies existed. In the fulness of time, the majority of such enterprises would go on to either merge or simply fail. Home never knew in advance how much money would be in his charge on any particular run, but the generous size of parcels he normally had to transport was a pretty good indication that the sums involved were likely to be considerable.

Pulling himself up onto the top of the coach, Home carefully deposited this final package into the cavernous mail box at the rear and took his seat there. In all, close to £7,000, equivalent to a little short of £1,000,000 in today’s money was aboard the coach that day. Home had been a mail coach guard on the Stirling to Edinburgh mail run for nigh on eight years and the entrusting of large quantities of bank notes to his care was a well-established routine.

With all the money parcels safely stowed and locked in the coach mail box they were ready to depart. Falkirk was the first stop en route, followed by Lauriston, Linlithgow, Winchburgh, Kirkliston, Corstorphine and then Edinburgh, their final destination. However, on this fateful day Home was to betray the trust bestowed upon him.

***

“Here, have some more ale, you look like you need something to help forget your woes.”

“It’ll tak' a darn sight mair nappy than that, man,” moaned Home. “I’ve bin a gowk mony times ower 'n' mah wife aye spends money lik' there’s na th'morra. Ah cannae keep mah secret fae her muckle langer. Whin she finds oot she’s sure tae gimme merry hell!”

“Not a happy union then, I take it?

“She’s Satan’s witch ah tell ye! ne'er a kind word 'n' aye duin wi' a tongue lashing."

This little

conversation had taken place some weeks earlier and Robert Murray saw straight

away the possibilities Home’s wretched predicament might present. Murray was a

smooth-talking and prosperous-looking man in his late 30’s and gifted with an

astute judgement of human nature of which he often made use for nefarious

purposes. Despite his polished English accent and dapper appearance, Murray had

a lifetime of criminal activity behind him and was always on the look-out for

the main chance; William Home was clearly ripe for plucking. A frequent patron

of 'The Auld Hundred' pub in Edinburgh’s Rose Street, all the regulars knew that

Home was the guard on the Stirling to Edinburgh mail coach.

A decent man at

heart, he was well-respected by those who thought they knew him well, but Home

had a serious addiction; he was an inveterate gambler, and an unsuccessful one

at that. With one mail coach robbery already under his belt, Murray was

immediately interested in his quarry and probed for any further weaknesses that

he might exploit.When Home had partaken of rather more ale than he could

handle and let slip he had serious gambling debts, Murray was seemingly most

sympathetic to his plight and offered to help him in whatever way he could. ‘A

friend in need is a friend indeed’ as the saying goes, and Home was most

certainly ‘in need’.

After a little more gentle probing, Murray gleaned that Home was a frequent punter at Edinburgh Racecourse in Musselburgh. Through sheer bad fortune, (but more probably, poor judgement), Home had experienced an horrendous run of losses. As is often the want of addicted gamblers, Home could not accept defeat and simply doubled-up on wagers which only served to compound his predicament.

“I’m the man to help you,” cried Murray. “I rarely lose a bet on horses thanks to the many inside contacts I have with jockeys and trainers. As long as I keep them sweet with a little payback from my winnings, they come up trumps time and time again.”

Like a drowning man clutching straws, Murray’s offer was too tempting for a man like Home who was ever-ready to see the best in people.

“Whit dae ye suggest then?”

“Why! Let’s both go to the next race meet and I’ll keep you right. I’ll advance you the stake money and you can reimburse me from your winnings.”

***

Five races into the card and Home had not had one single win. An outwardly embarrassed Murray swore he’d never known such ill fortune and offered the poor man yet another sizeable stake for the final race. Unsurprisingly, Home’s horse fell at the first hurdle and was a ripe candidate for the glue factory after breaking a leg. With a considerable sum of money now owing to Murray in addition to his other creditors, Home's situation was even more desperate. Murray, of course, had secretly placed his own wagers on the successful mounts and was more than recompensed for the money he’d given to Home. Home was a broken man and in deep despair.

“We’ll be evicted fae oor tenement 'n' mah wife wull hate me forever,” wailed Home. “Ah micht juist as weel end it a' noo!”

“Now, now, William,” said Home as he placed a consoling arm across the man’s shoulders. “I’m sure we can still come up with a solution to your plight. Just give me a few days to think it over and I’ll see what I can do.”

Murray didn’t need any time to formulate his plan, it had been ready and waiting since the moment he first learned of Home’s gambling addiction.

A few days later, Home was making his way across Edinburgh’s St Andrew Square to visit The Auld Hundred where he intended to drown his sorrows yet again if the landlord was still agreeable to ‘put it on the slate’. To his surprise and joy, Murray appeared by his side, but the expression on the man’s face was grave.

“William, I’ve had some serious tidings; in fact, I’m in a spot of bother.”

This wasn’t the news Home had been hoping to hear from someone who’d more or less promised to ease his worries.

“Some of my investments have gone bad and my finances are no longer as I would wish. In fact, I’m being pressed by some rum coves to honour a substantial debt before the end of the year.”

Home’s heart sank, so he wasn’t going to get any further help from Murray after all. However, there were more bad tidings.

“I don’t like to press upon such a good friend as yourself William, but I desperately need to ask for the return of the money I advanced you at Musselburgh.”

It was as if Home had been struck with a sledgehammer; this was the last thing he needed to hear.

“Bit ah haven’t a penny tae mah name, Rabbie. I’m awready in debt tae mair folk than ah care tae batch. If ye insist oan yer money noo, it's th' Debtors’ Jyle fur me 'n' i’ll ne'er be able tae pay mah wey oot o' that kind o' hell-hole!”

“Then we’re both in a pretty pickle William, the pair of us could be cellmates in the Debtors' Gaol if you can’t help me.”

The anguished look on Murray’s face hurt Home to the quick. “I’d dae anythin' tae hulp ye Rabbie, bit I'm sae deep in debt ah can’t see ony wey ever tae pay ye back.”

“This is truly a desperate situation then, William. I can think of only one course of action to rescue us both from this sorry mess,” and then the trap was sprung.

To Home’s

consternation, Murray began to steer him towards a noted brothel in North St David Street, a mere stone's throw from where they had been standing.“Ah kin hae mony weaknesses Rabbie, bit I’ve na truck wi' a hoose o' ill repute sic as this.”

Still bewildered and in a state of turmoil after Murray’s devastating news, Home was too befuddled to resist.

Once inside the brothel, Murray ushered Home to a secluded nook where they could speak without being overheard. “Two pints of ale, if you please Mary,” called Murray to a raddled looking doxie who hovered close by.

“Nothing else the day then, Mr Robert?” she enquired with a knowing leer. An oblique look from Murray was sufficient to send her flouncing off and return swiftly with two tankards foaming to the brim.

Murray then began to outline his plan which would supposedly be the answer to all their troubles.

***

As the mail coach arrived at Winchburgh, a mere 12 miles from Edinburgh, Home unlocked the coach mail box and placed inside a bag of parcels he’d collected earlier at Falkirk. The parcels containing the bank notes were now sitting on the left side of the mail box where Murray had previously instructed him to place them. This was the moment when he was at a crossroads in life; if he relocked the mail box he would remain an honest man, if he didn’t, he would be forever tainted by a deed that would live on in infamy.

The next stop was the village of Kirkliston where the final change of horses was to take place while Home dealt with the post. The ritual of changing horses took place roughly every 6 or 8 miles with a succession of coaching inns fulfilling that role. Unbeknown to the passengers on board and the staff at the Kirkliston Inn, two felons would be lying in wait to steal the contents of the unlocked coach mail box.

The plan to rob the mail coach was relatively simple. Murray and two accomplices would set off on a horse-drawn gig from South Queensferry, a couple of miles north of Kirkliston, and time their arrival at the village coach inn shortly before the mail coach was due to arrive. Under cover of darkness, one of the two accomplices would scale the rear of the mail coach and take whatever parcels lay on the left-hand side of the mailbox while Home was engaged with his mail duties. To ensure there was sufficient time to carry out the heist, Home would assist with the changing of the horses and spend some time in the stables at the rear of the inn. Meanwhile, Murray would be waiting in the gig a little way off just beyond Loanhead on the South Queensferry road which was to be their escape route. Timing was crucial; If the mail coach was late, two strangers loitering around the village might arouse the suspicions of the locals who were always on the alert for the predations of the 'Resurrection Men' who had already snatched at least two bodies from the local kirk graveyard in recent years. If the mail coach arrived too early, Murray and his accomplices would miss their rendezvous, but this was unlikely as Murray had had several weeks to fine-tune his plan. He’d reconnoitred the road between Kirkliston and South Queensferry several times during daylight and knew exactly how long a gig should take to make the journey. After the robbery, Murray and his two accomplices would eventually continue on to Edinburgh where they could safely lose themselves in the metropolis. Of course, all of this depended on a succession of variables falling into place as expected, but in the words of the bard Rabbie Burns, a man who’d stayed at Kirkliston Inn several years earlier, ‘The best laid schemes o’mice an’ men gang aft a-gley.'

Earlier on the day of the robbery, Murray went to hire a gig from his regular supplier, Smith’s Stables in Rose Street, Edinburgh, but to his consternation the only gig available had no lamps, a serious setback with a night time journey ahead of him. Outside the gig stables, Murray’s two confederates were waiting. William Darling and Alistair Fairlie were a couple of local villains whose acquaintance Murray had made in the St David Street brothel. Both in their late twenties, the two men were strongly built, just the sort of ruffians needed by Murray who was of slight frame and of little use in a brawl. They were not impressed when they saw the lamp-less gig and the tired-looking nag harnessed between the shafts.

“Is this the best ye can do Murray!” cried Fairlie. “I thought ye knew whit ye was aboot in these matters. This nags a’ready oot on its feet!”

“Dinnae fesh y’sel Ally, Mr Murray ken’s whit he’s aboot. A’ve nay worries we’ll see this wee bit o’business through.”

“You’re absolutely correct, Will. I’ve got the whole scheme planned to the last detail. Nothing will stop us making our fortunes as long as Home keeps his end of the bargain, and of that I’m more than certain. He’s like a prize salmon hooked deep.”

***

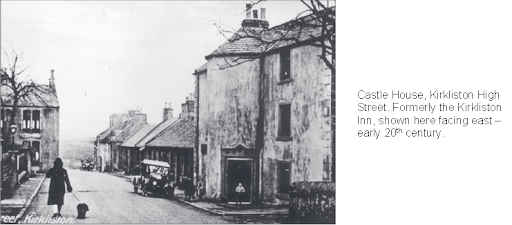

What meagre light cast by the waning crescent of the moon was masked by the dense cloud-cover over West Lothian. As the mail coach plunged through the pitch-black darkness, the driver became aware of a gig trailing in his wake. Highwaymen were an ever-present hazard on the mail coach routes and the driver hoped that Home had the guns in his sword case well-primed and at the ready should any assault on their coach be forthcoming. He need not have worried though. Colin Laing, a merchant from far-off Gloucestershire was making his way to Edinburgh. Carrying a considerable sum in cash and bills, he whipped his gig on to keep company with the mail coach. Safety in numbers was his hope and the proximity of the mail coach would provide him with some measure of security. Home had also noted the following gig and was both confused and troubled. Surely, this wasn’t the scheme he and Murray had decided upon? There was no more time for him to agonise as the driver blew on his horn to warn of their imminent arrival at Kirkliston Inn, a substantial turreted building which also served as a lodgings adjoining the Post Office. Its peeling coat of white limewash gave it an air of dilapidation, hardly surprising for a building dating back to the 17th century. As the coach ended its slow climb up Path Brae, the western approach to Kirkliston, the driver steered the vehicle over to the right-hand side of the road where the inn stood while Home looked around anxiously for any sign of his confederates who were supposed to be lying in wait.

***

Darling and Fairlie were worried. They had been skulking in the shadows opposite the coach inn for almost 30 minutes and there was still no sign of the mail coach which was late.

“Ah don’t lik' this yin wee bit,” murmured Darling. “We mist hae arrived tae late 'n' th' coach haes awready gaen.”

“Best ye tak' a keek o'er th' road 'n' ask someone then,” suggested Fairlie. “Else wur oan a fool’s errand 'ere.”

Darling swiftly made his way across and disappeared behind the inn to speak to the hostlers in the stables, they would be sure to know the answer.

***

The village was cloaked in pitch-black darkness and few people were abroad on this cold December evening excepting a few hardly souls who relished the distraction of the spectacle a visiting mail coach afforded on such occasions. With a suspicious eye on the following gig which had come to a halt behind them, Home and the driver climbed down and set about their business. For Home, it was a matter of collecting post; for the driver, with the assistance of the inn hostlers, the changing of the tired beasts for fresh horses was his prime concern. This would be the final change of horses for the last two legs of the journey to Edinburgh, and it was during this break that one of Murray’s confederates would scale the rear of the coach and relieve the mail box of its money parcels. But, where were they?

Matthew Linn, the Kirkliston postmaster was waiting at the door of the Post Office for Home. Both men knew each other well and it was usual for them to exchange a little craic inside during the collection of the post. This was an ideal opportunity for Home to delay a while to enable the robbery to take place. But, once he’d collected the mail bag, Home could still see no sign of the would-be robbers. Seizing the halters of the leading pair of horses, he began to assist in attaching their harnesses to the coach. This delaying tactic would give the felons a few extra precious minutes in which to carry out their villainous deed if need be. To Home’s relief, the driver of the following gig had now gone into the stables to replace his own horse as the hostlers were still busy with the coach team, so that was one potential witness out of the equation. While all of this activity was taking place, Darling had dashed out on to the street now he’d heard the coach arrive. Fairlie had already scaled the rear of the vehicle and was tossing the bank note parcels from inside the left of the mail box down to the opposite side of the coach where no one could see what was happening. The chilled outside passengers atop the coach were too preoccupied with the activity at the inn and deciding whether to purchase the hot toddies being offered up by one of the inn staff to notice the heist. William Darling was now waiting below and as Fairlie jumped down, the two men gathered up the parcels and swiftly made their way across the road into the Backlands of Kirkliston, an area of open ground and scattered flax weavers’ dwellings which followed a parallel course to the Queensferry road where Murray was waiting for them. With some difficulty they managed to locate the gig waiting in the pitch darkness and hurriedly tossed the parcels they’d stolen on board. Leaping up beside Murray on the seat, they clapped each other on the back with elation and relief.

“That wis th' sweetest 'n' easiest night’s wirk I’ve ever dane!” chuckled Darling, “You’re a genius Mr Murray, o' that there’s na doubt.”

“We’ll have plenty of time to celebrate later, boys,” cautioned Murray. “Now’s the moment to put some distance between ourselves and the village.” With that, he flicked his whip across the horse’s rump and they set off at a cracking pace.

Murray may have had many talents, but horse management was not amongst them, especially on a pitch-black night with no lamps to light the way. Scarcely 100 yards along the uneven and heavily-rutted road the nag veered alarmingly to the right and dropped a wheel into the adjoining ditch. This violent manoeuvre immediately spilled the contents of the gig along the road as it careered on out of control for another three or four hundred yards with the men clinging on desperately before it struck a large boulder and bounced into a deep ditch just past the newly-built South Lodge of the adjoining Dundas Estate. Bruised and shaken, the three men clambered out of the ruins of the gig while the poor horse remained trapped in its traces, quivering with terror and shock.

“Where are the packages?” shouted Murray. ”Didn’t you keep a proper hold of them you fools?”

“Dinnae huv a go casting blame oan us, Murray!” shouted Fairlie. “Yer damn gowk driving 'n' this ramshackle gig ur yer fault, 'n' na yin else’s!”

“Wheesht yer havering, Fairley! Th' packets ur someways back thare alang th' road 'n' we’ll juist hae tae track back 'n' fin' thaim, otherwise this night’s wirk wull hae bin fur hee haw.” Darling’s wise words brought the other two men back to their senses, so, abandoning the smashed gig and distressed horse, all three picked their way back towards Kirkliston, hoping against hope that they could recover their booty.

***

As Home finally emerged from the inn stables, he got a fright to see one of his inside passengers walking back to the coach. Much to his relief, a brief conversation with the gentleman confirmed he’d not been aware that a robbery was taking place. In fact, the man was an acquaintance of Colin Laing, the driver of the following gig. He’d noticed Laing on his way to change his horse and had simply stepped out of the coach to have a chat with the gentleman.

With all the passengers now safely on board, Home climbed back into his seat and reached down into the mail box to stow the bag he’d collected earlier. His face was grim as he noted the parcels of bank notes had gone. The deed was done; there was no way back for him now. Even the prospect of clearing his debts with the share of the money that Murray had promised him was of little consolation. The die was cast and he was now a common criminal, no better than those he’d scorned and despised throughout his life.

***

On the Kirkliston to Queensferry road, a couple of farm labourers were making their way home on foot from the village back to Milton Farm, a little under two miles from Kirkliston.

On reaching the spot where Murray had been waiting with his gig earlier, they noted the sound of a horn announcing the departure of the Stirling to Edinburgh mail coach. A few hundred yards further on, John Leach, one of the two farm workers, found a light-coloured great-coat lying on the road. Soon after that, two men came up from behind, each carrying a small bundle under their arms. Hearing voices approaching, Darling and Fairlie had been crouching in the roadside ditch, but soon realised they needed to make their way up the road without further delay. Catching up with the farm workers, neither man said anything to Leach or his companion Thomas Boyd, but quickly continued past into the enveloping darkness. A little further on, the farm workers came across another two heavy cloaks lying in the road which the two strangers ahead of them had evidently failed to notice. Amongst various items they discovered on searching the pockets was a small parcel wrapped in paper which had a soft feel. It was simply one of the ubiquitous Kirkliston cheese sandwiches (for which the village may have gained the nickname ‘Cheesetown’) that Darling had bought at the inn while he was checking whether the coach had already left, not one of the money parcels. At that moment an anxious and breathless Robert Murray came upon the scene demanding the cloaks as he asserted they were his property. Putting on a false Scots accent, he managed to convince the two farm workers that the cloaks had fallen out of his gig so they handed them over, but not before eliciting a shilling from him for their trouble. In the fullness of time, it was fortunate for Murray that it was too dark for the men to make out his features during their encounter.

***

“I’m na goin’ back alang that road agin th' nicht, Murray. Ye kin gang alang yersel if ye lik'!” raged Fairlie.

“But there’s a small fortune still lying out there waiting to be found. If you don’t hurry back now, one of those country simpletons we hid from earlier will find it before you!”

“Ah tell ye, I’m nae goin’ back alang thare, 'n' that’s final!”

William Darling wasn’t for retracing his steps either. Besides, that would leave Murray alone with the two money parcels they’d managed to retrieve, and what would prevent him from disappearing while they were out searching in the darkness? Although the third parcel still lay somewhere along the Kirkliston road, the money they now had in their possession was a princely sum indeed!

Murray and his

confederates were ensconced in the Newhalls Inn, South Queensferry. Weary and

mud-spattered, the three men weren’t sure they felt elated or disconsolate.

Yes, they had recovered the lion’s share of their booty, but the missing third

parcel rankled and they’d also been badly shaken up when the gig had crashed.

Their plans for a swift escape to Edinburgh were now in disarray, but Murray

still had his wits about him.

“I can hire a post chaise here in town and we can take our planned route back to Edinburgh.”

“Nae oan yer lee, Murray!” snarled Fairlie. “There’ll be hue 'n' cry aboot th' robbery by th' time we git back 'n' th' polis wull be keekin oot fur a'body arriving at this late oor. A'm waantin' mah share o' th' cash noo 'n' be oan mah wey. I’ve kin in Bo’ness 'n' they’ll fin' me a berth oan a ship tae ither bits whaur i’ll be weel awa' fae th' scene.”

Darling wasn’t so keen on Fairlie’s plan; he was in favour of Murray’s suggestion and taking his chances on returning to Edinburgh that night.

“So be it, then,” agreed Murray. “Let’s find a quiet corner and divvy up the money so you can be on your way.”

Finishing their ale, the three men made their way out into the night and began looking for a suitable place to open the two parcels. After a little searching, they found a small, empty hut on the harbour wall that reaped the benefit of the town lights reflecting off the water in the harbour. Laying the parcels on a wooden bench inside the hut, they tore the paper wrappers off and began to decant the notes into three neat piles on the bench; three piles only, because Murray had never countenanced giving Home his share of the booty and planned to be well away from Edinburgh before Home realised his folly in trusting a man like himself. Each man then wrapped their share of the notes into their neckcloths and bound them up with some of the string from the original parcels.

“Just in case I cannot hire a chaise this evening Will, best you take off along the Edinburgh road now,” suggested Murray. “If I’m successful, I’ll keep an eye open for you along the road and you can join me then.”

Darling was not entirely happy with Murray’s suggestion and the prospect of a lengthy walk back to town, but with his share of the money tucked securely into his regained muddy greatcoat, he decided to go along with the plan. Meanwhile, Fairlie was already striding off for the long walk to Bo’ness where he was hoping to rouse his kinfolk on arrival, despite the likelihood of it being in the small hours when he got there.

Murray was in luck for once. He was able to secure a chaise at Newhalls Inn and the two men set off for Edinburgh forthwith. A little way along, Darling was waiting at the roadside so Murray ordered the driver, Alexander Adams, to stop and let Darling join him inside the coach. Eventually, both passengers alighted at Stockbridge in Edinburgh and parted company. Murray knew that the smashed gig was potentially incriminating evidence and that he needed to leave Edinburgh as soon as possible. Later that evening he returned to Smith’s Stables in Rose Street to report his accident and buy himself a little more time before the news of the robbery could be linked to himself. David Ince, hostler to Smith’s Stables wanted Murray to take him to the scene of the accident forthwith, but Murray said he had to leave town urgently to attend the funeral of a close relative. Ince was left with little option but to set off alone in search of the missing gig while Murray assured Joseph Smith the owner that he would pay for the damage the next day. As Murray was a regular customer, Smith reluctantly agreed to this suggestion.

***

Tellingly, despite halting at Corstorphine, Home had still not revealed to anyone that the money parcels were missing. It was not until he reached the Post Office in Edinburgh where the representatives of the various banks were waiting that he was obliged to confess the appalling news of the robbery.

Edinburgh Post Office (1819)

16-20 Waterloo Place

©The Saturday Gallery

As Home sheepishly explained the theft to the astonished banks’ agents, he claimed he had been in such a state of alarm and confusion that he had not known what he was doing until the end of the journey. He further averred that he had no idea how the robbery had been effected, other than it must have been at Kirkliston because that was the only point when the mail box had been unlocked while he was away from the coach.

***

The day after the robbery, Thomas Boyd and another companion, James Spaddle set off from Milton Farm to attend Sunday service at Kirkliston Parish Kirk. They had barely walked half a mile when they came across the broken gig and exhausted horse lodged in the deep roadside ditch. It was surprising that Boyd and his companion from the night before had not spotted the gig and horse there, but the ditch was very deep and the night had been black. The name of the gig’s owner was very clearly etched on the remnants of the smashed conveyance, so after taking the poor nag to Milton Farm and giving it some much-needed care and attention Boyd set off to return the creature to its rightful owner in Rose Street, Edinburgh, no doubt hoping for a reward for his trouble.

It was a relieved Joseph Smith who took delivery of his horse that Sunday and gave the Kirkliston farmhand Thomas Boyd a handsome tip for his honestly and trouble, but there was still the matter of the missing gig. Knowing that Murray lodged a few doors down Rose Street with a Mrs Wilson, he went and paid him a visit that morning. He was lucky; Murray had not yet taken flight and was still in the process of packing a few of his belongings. As the true cost of the damaged gig was still to be ascertained, Smith accepted a down payment of £40 as a token of good faith. Mrs Wilson was not so fortunate later that morning as Murray departed still owing her six weeks’ rent for his lodgings.

In an attempt to cover his tracks, Murray hired transport to nearby Musselburgh from where he hoped to catch a mail coach which would take him far away from the scene. On being informed by the locals that he’d have to purchase a ticket back in Edinburgh in order to board a mail coach Murray had no alternative but to retrace his steps. His plan to escape across the border to England was now becoming ever more time-consuming and complex. Yet again, Murray’s cunning and long criminal experience came into play. At the mail coach office he used an alias when purchasing his ticket; Graham was a name he'd employed in the past and it was under this guise he made good his escape from Scotland and the clutches of the law, or so he thought …

Part Two of this story is now available on the Kirkliston Heritage Blogspot. Reader, be prepared for a tale with an incredible twist in it's tail!

A P George

Kirkliston Heritage Society

SOURCES AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Alamy Photos

Astropixles

Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, January 2nd, 1825

Caledonian Mercury, March 3rd, 1825

Canmore ID 117824

Images of Scotland - Kirkliston, The History Press, 2022 (ISBN 978 0 7524 1131 6)

National Library of Scotland

Newcastle Courant, December 25th, 1824

Sir Jack Stewart-Clark, owner of Dundas Estates

Jill Price, Account and Planning Manager, Dundas Estates

The Edinburgh Annual Register, January, 1825

The Saturday Gallery

The Word on the Street, 1820-1830

Wikipedia

No comments:

Post a Comment